Molchat Doma and the Midwest Connection

The Midwest and Eastern Europe share a traumatic history in the era of the "shock doctrine" and neoliberalism. This could be why so many Ohioans like Molchat Doma.

“Kemba Live!” is a music venue in Columbus, Ohio that fits over two thousand sweaty Midwesterners in their indoor facility just west of downtown. The dozen or so acts on the upcoming calendar include Father John Misty, Fontaines D.C., and the Dropkick Murphys. One of the most recent performances was the Belarusian Synth Wave band, Molchat Doma, which garnered a crowd of similar or larger size to the last Dropkick Murphys show, which had, to their advantage, a number of tickets reserved at a discount for union members connected to the Central Labor Council of Columbus.

There has been little printed material used, whether humorous or instructive, about the parallels between Eastern Europe and the Midwestern United States, which someone (Walter Mondale) once designated as the “Rust Belt,” originally misquoted by the press as the “Rust Bowl.” The “Great Lakes Megaregion” would be the epithet I would’ve picked if anyone would’ve bothered to ask. Or perhaps something funnier—Rust Bowl is certainly in the right direction.

Whether one calls it the “Rust Belt” or the “Great Lakes Megaregion” or something funnier to be determined at a later date, no one can deny that the region which is home to a declining economy, one accelerated in its degradation by the Reagan era. It’s a trauma shared in a seemingly ethereal way, a negatively ethereal way, with Eastern Europe.

Every day, throughout this vast land of ours, on the plains, lakes, and the sliver of Appalachia that lines the Eastern third of the state of Ohio, there are toiling proletarians streaming more Belarusian synth wave music and Russian hard bass than European countries, with all their urban clubs and disenchanted middle-class, could ever dream of.

And yet, does anyone ever write Op-Eds on the connection? Other than occasional doomer memes comparing the two, what discourse, in any legitimate capacity, exists? I certainly hope none, for I rather hope to carve out a literary trail in this spatio-cultural field.

There are three primary bonds between Eastern Europe and the Midwest: (1) Political economy, which, in the Midwest means de-industrialization and the rise of right-wing populism, and in Eastern Europe means the fall of Communism and capitalism’s economic catastrophe that led to the largest peace-time decline in a population’s life expectancy. (2) Geography, or the manifestations associated with ones distance from the equator and the earthworks that come about (waterways, mountains, and the lack of both). (3) Atmosphere, mostly in the winter, which has yet to fascinate anyone to the point of making a trip from other more tropical regions. And then of course there’s the culture.

Of the many film parallels of the late 20th century that could be formulated—Paul Schrader movies and Lilya 4 Ever (2002) are certainly among them—perhaps the most illuminating and comprehensive connection is, of course, the Russian films Brother (1997) and Brother 2 (2000).

Brother is a neo-noir crime drama that follows Danila Bagrov (played by Sergei Bodrov Jr.) returning home from the Chechen War. Seeking work with his brother in St. Petersburg, who happens to be a contract killer, Danila quickly becomes involved in a major plot to kill a mafia boss.

The film is a monumental middle finger to the spectacular fantasy of the “happy 90s,” showing a St. Petersburg riddled with toiling locals selling their own clothes on the streets in order to afford hyper-inflated grocery costs and rent. Brother exposed the harsh realities of the “shock doctrine” policies that sold off publicly-owned industries to oligarchs, devastating the economy for working-class Russians (a central focus of Adam Curtis’ Part Five of his 2022 docu-series TraumaZone). But the sequel goes a step further.

In Brother 2, similar to Leningrad Cowboys Go America, the protagonist makes the trip to America. Unlike Leningrad Cowboys Go America, however, Danila goes to help a friend who plays professional hockey. Arriving in Chicago, he finds a harsh city not dissimilar from the grey landscape of a mob-run St. Petersburg—his hockey player friend is being extorted by a local American finance capitalist. In the pivotal scene in which Danila confronts him in a skyscraper, he challenges whether the key to power is money.

“I think that power is in truth,” Danila says. “Whoever has right on their side is stronger.” The scene quickly cuts to Danila handing the money over to his hockey player friend, seemingly giving credence to Mao’s famous quote about political power growing out of the barrel of a gun.

For us Midwesterners today, it is clear that the words “capitalism” and “democracy” involve numerous contradictions, for capitalism means control by those who own the corporations and the factories, in other words, by those other than us who are being controlled. When Ohio’s Reagan, Governor Jim Rhodes, served as governor for sixteen years, gutting the nanny state in favor of private ownership, he sold out the people in a way familiar to those in Yeltsin’s Russia. The appearance, that of a free world, is a misleading fantasy of biblical proportions.

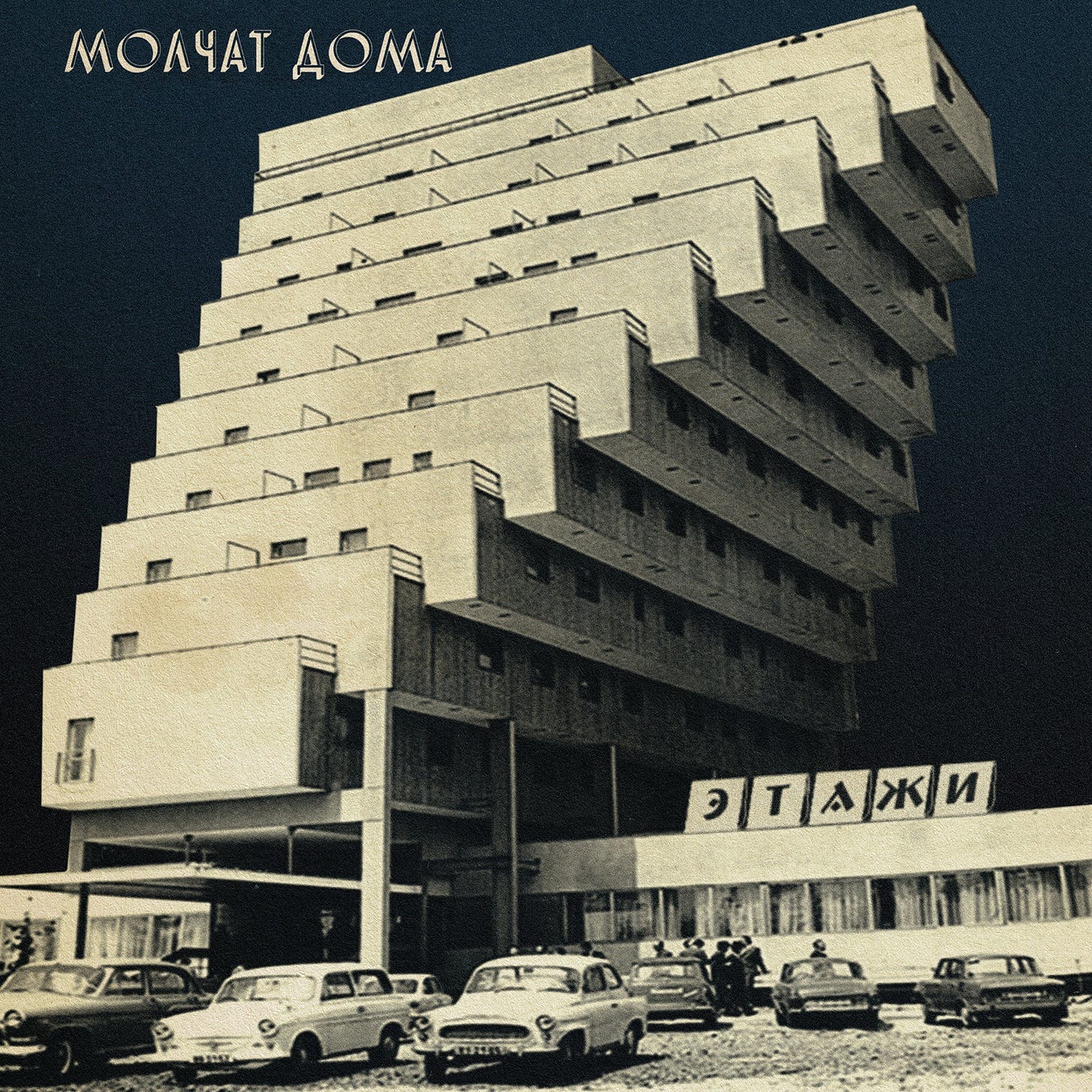

Of the appeal of Molchat Doma to Midwesterners, a band whose album covers depict architectural marvels from Communist countries and whose sounds are associated with perestroika-era Soviet synth wave, it will only accelerate in the Trump years, a time which is already daily being discredited by an unbroken record of truth and history.

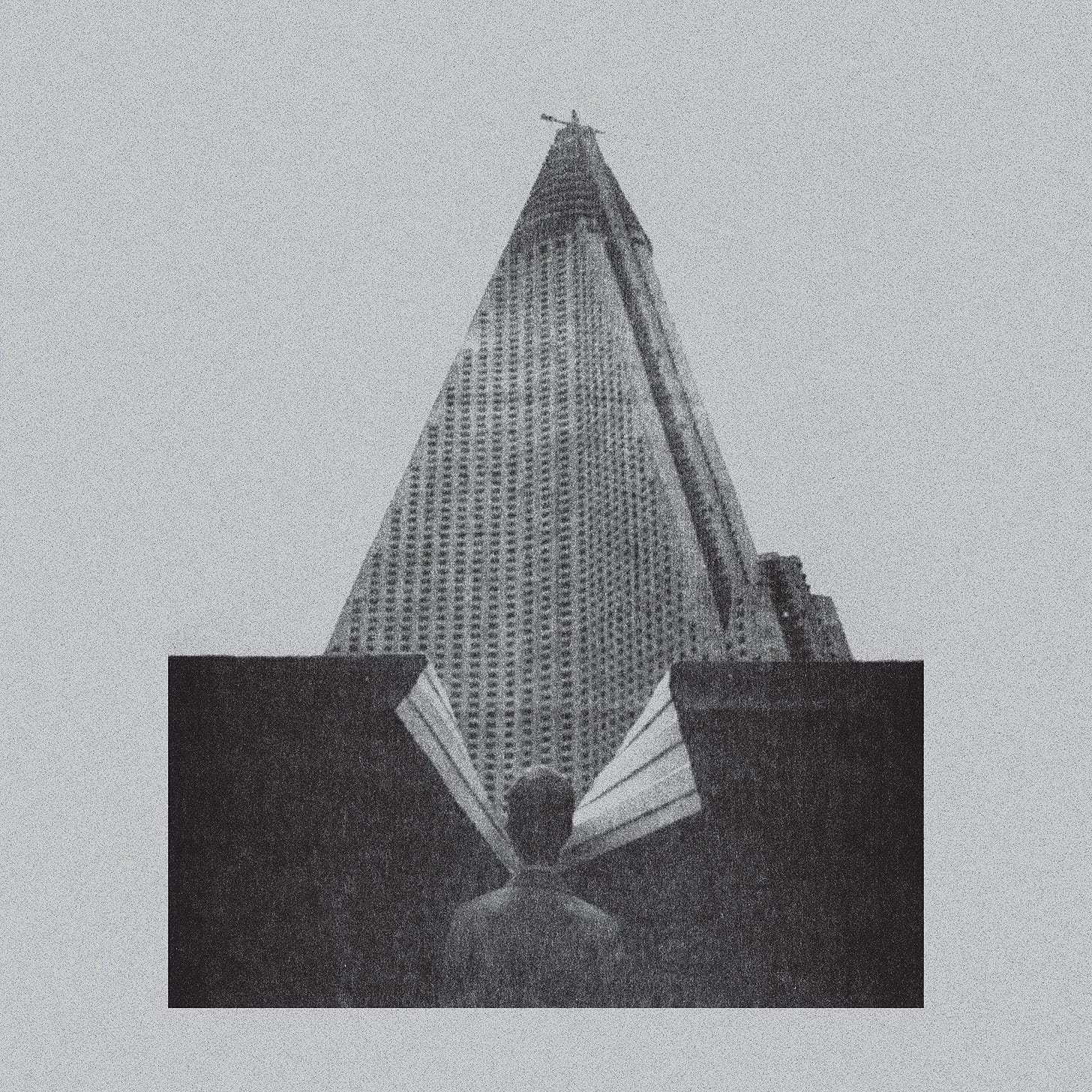

My interest is far less in the band’s ideology, they literally have a song called “I am not a Communist,” but instead in the utopian underpinnings of the communist aesthetics; the unrealized politics of socialist synth wave. It’s a utopianism lying dormant in the music, but also the architecture of their art. The album cover for From Our Houses Rooftops, for example, is a picture of the Ryugyong Hotel in North Korea, a monumental pyramid that’s never been finished due to the economic crisis caused by the fall of the Soviet Union.

It’s not, as is often argued, a reflection of the Soviet era, which the band members didn’t live through, but instead a disatisfaction with the implentation of capitalism in Eastern Europe (and the curious state of Belarus, which is still run by their Communist Party). It’s telling that if they would’ve used brutalist architecture from the same time period in Ohio, it would be buildings funded by former Governor Rhodes who, wishing to have his name on infrastructure projects, built a number of brutalist buildings but just so happened to refuse funding for the occupants (in contrast to Soviet buildings that housed cultural centers and heavily subsidized apartments). The ideologies are baked into the architecture and the music. The economic distaste for capitalism is a yearning that resonates with many Americans in general, but more specifically those of us in the Rust Belt, especially those in red states like Ohio who, without any political control, watch in despair as our rights are stripped away year after year.

I stood politely towards the rear of “Kemba Live!” for Molchat Doma’s show, a choice largely having to do with my height. It was from that vantage point that I watched a man singing in Russian move flannel-wearing millennials wearing Columbus Blue Jackets hats and Gen-Zers with black and white facepaint to drift side to side. “Spasibo,” the singer said after every song, not knowing any English other than, “Thank you very much, we are Molchat Doma from Minsk.” After one such “spasibo,” on of the of the flannels shouted back, “spasibo mother fucker.” It was at that moment that the political-economy, geography, and atmosphere of the Midwest and Eastern Europe synthesized into a shared ethereal experience throughout the plains, lakes, and the sliver of Appalachia that lines the Eastern third of the state of Ohio—a largely negative shared ethereal experience. Perhaps it will one day be recalled as the beginning of the end of the Rust Belt era of the Midwest. I certainly hope so, for this article would be remembered as the one that carved out a literary trail in the spatio-cultural field.