On Communist Letters

In an age where the art of correspondence is lost, the letters of American Communist writers like Dalton Trumbo remind us of a time when wit and conviction were wielded with revolutionary spirit.

In a world more painfully connected than ever, the art of letter writing and journaling is a dying craft. Gone are the days where one's daily dispatches are organized in physical paragraphs crafted exclusively for the eyes of the recipient. No more gentle letters to young fans or agitated rebuttals to elderly foes, no, only shorthanded half hearted tweets and apology statements crafted professionally by teams of public relations specialists. The great writers of our time can sleep easy knowing that there will be no sudden unearthing of private correspondences published permanently in an edition of that frightening two-word specter, one’s posthumously published “Collected Letters”—and gone are the the egotistical bunch whose letters were laboriously formulated with the hope of one day being broadcasted. I’m not terribly upset about this fact—there are very few cultural figures today whose letters I’d want to read in the first place—but I’ve found myself with a growing list of letters I need to write and a flourishing collection of typewriters to type them. This has brought me back to the books of “Collected Letters” I own, most of which just so happen to be American Communist writers. And while I’ve found them to be valuable and charming, there are others, specifically James Thurber, who thought otherwise.

Trumbo’s Alarm

No blacklisted Communist from the 1950s has ever fully recovered from that Red Scare era of censorship and historical revisionism. Yes, you will learn about the Hollywood Ten, but only its existence as a historical fact. How many could name a single member of those called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and how many of their works? Only one name has been resurrected in a meaningful way this century, only one has found himself promoted, even if it’s to a modest degree, by today's Hollywood elites. I’m speaking of course of that rambunctious mustache-growing American, the author of the novel Johnny Got His Gun and the screenplay for Roman Holiday: the tragically unapologetic Dalton Trumbo.

In the 2015 film, Trumbo, Brian Cranston plays Trumbo as he and his friends are blacklisted for their political beliefs and activism in and around the Communist Party. Based on the 1977 Bruce Cook biography of the same name, the film shows how Trumbo is able to break the with the 1960 film Spartacus, the opening credits of which openly display the name of two Communists: Howard Fast, the author of the novel that the film is based, and Dalton Trumbo, who had, at least during the period of the blacklists, resorted to using a web of fake and, with the permission of others, real, names. (When I published an article about Spartacus breaking the blacklists, his daughter Mitzi Trumbo messaged me on Facebook taking issue with my referring to him as a radical Communist. I clarified that I meant it only as an affectionate compliment.)

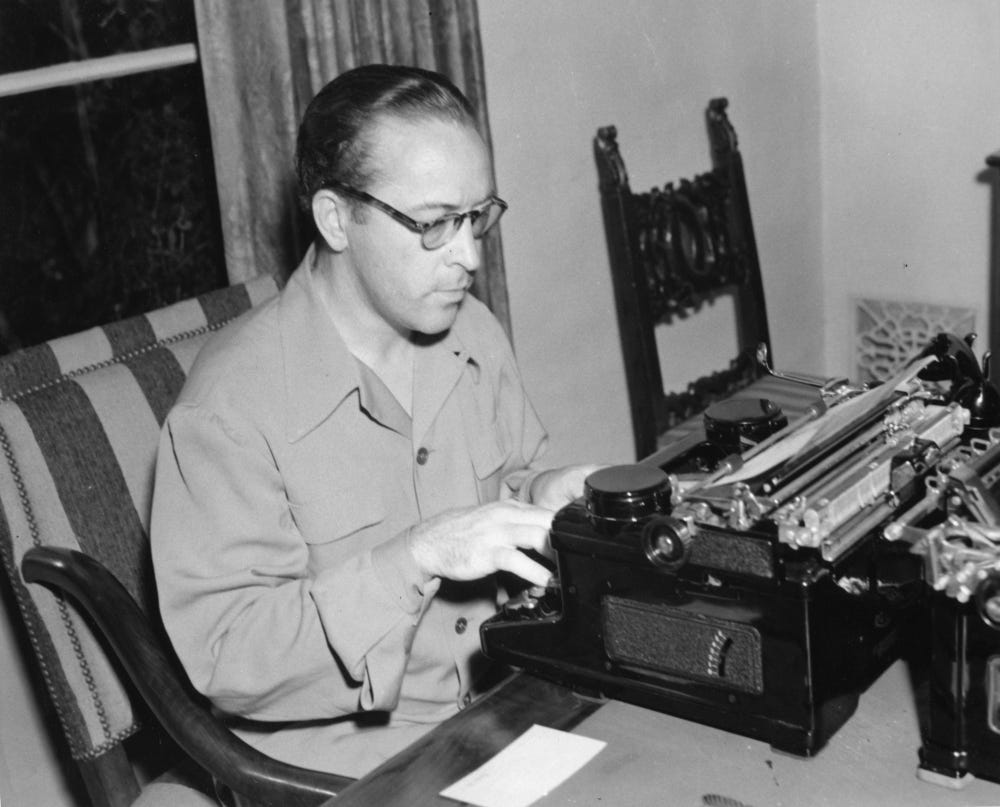

Dalton Trumbo was a sneering architect of letters who, with wit and fury, crafted testimonies of contradiction in a world of American idealism and his relentless pull of personal conviction. He was, to put it simply, both funny and personable. A 2007 documentary also called Trumbo emphasized that the writer should be remembered not only for his films, but also his letters. The actor Paul Giamatti reads a series of letters sent to a telephone company that has charged him a steep price for their services:

Dear burglars,

[…] When we Reds come into power we are going to shoot merchants in the following order: (1) those who are greedy, and (2) those who are witty. Since you fall into both categories it will be a sad story when we finally lay hands on you. [...] Naturally I hope this will be the last time I shall be obliged to do business with you… Please extend my good wishes for the holiday season to everyone in the thuggery.

I found this series of letters printed in the long out-of-print Additional Dialogues: Letters of Dalton Trumbo, 1942-1962 (1970), a prized possession gifted to me as a birthday present. The 600 page collection is not one filled with lengthy Marxist debates and jargon, but rather simple and painfully, although welcomely so, mundane letters.

Odets and Hammett

One summer I joined my girlfriend’s family on a vacation on America’s third coast, the Great Lakes. It was the perfect time of year to visit northwest Michigan—the weather was ideal, the location, although a tourist town (Frankfort), was not too crowded, and the timing lined up perfectly in regards to taking time off work. There was, however, one issue: we weren’t able to fit in the house. A large tent was ordered and with it, a queen size inflatable mattress. I naturally brought with me more than a dozen books, but only one I read everyday in that deflated mattress. In the morning, when the ground was still moist and the sun had risen enough to provide a light source for the text, I’d open The Time is Ripe: The 1940 Journal of Clifford Odets.

Clifford Odets, a Communist playwright who wrote Waiting for Lefty, did not have a reputation for being mundane or apolitical. In Arthur Miller’s 1987 autobiography, Timebends, he described Odets as “an American romantic, as much a Broadway guy as a proletarian leader, probably more so.” The artist was obsessed both with socialism and earning a platform as an artist. “To call him contradictory,” Miller reflected, “is merely to say he was very much alive and a sufferer.” Knowing that Odets was considered one of the more dedicated Communist playwrights, I returned meticulously each day to his 1940 journal hoping for some wealth of Marxist cultural theory. Instead, I found modest personal reflections and painfully honest toiling.

On Friday, June 28, 1940, Odets wrote, “I am a painted man on a painted sea. Sea? No, swamp.” In addition to his bleak theses, there also flows sataric political reflections and constant reflections on improving his skills in writing. In one entry, he described the competitors of the Republican presidential candidates as “a handful of sweet potatoes, unshaped, lumpy, expressionless, so mild.” Reflecting on his writing of half of an act of a play, he confessed that “[i]t suddenly occurs to me that I am trying to pull off the inevitable: learning to write.”

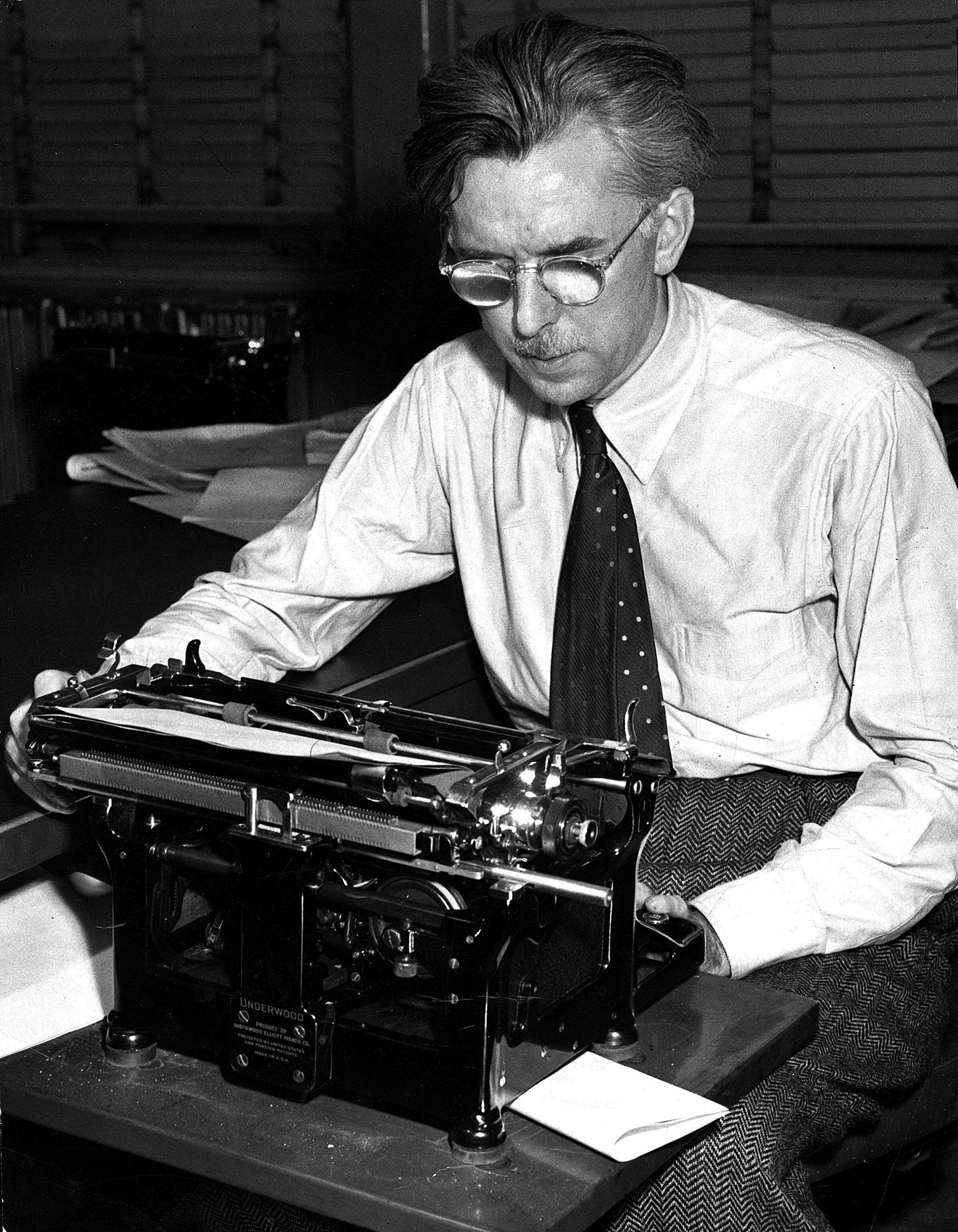

A similar trend plays out in the Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett. The famous detective novelist who wrote books like The Maltese Falcon and The Thin Man eventually joined the Communist Party and dumped much of his time into organizing. His letters are tender, personal, and, in some cases, echoing Trumbo, he’s desperately pleading for money. “IN DESPERATE NEED OF ALL THE MONEY I CAN FIND,” Hammett wrote in a telegram to his publisher in April, 1931. “CAN YOU DEPOSIT THOUSAND DOLLARS IN MY ACCOUNT.”

The next two letters are to his wife, the playwright Lillian Hellman. “Angel, It was nice of you to phone me, even if you did have to get plastered to do it,” he starts the letter. He ends it with: “So you’re not coming home, eh? I suppose it doesn’t make any difference if I have to go on practically masturbating!” It’s not just in the sexual realm that Hammett was hurting, but again in the financial one. The next two letters are again to his publisher, one thanking them for the thousand dollars and the next: “WANT TO RETURN TO NEWYORK NEXT WEEK BUT AM IN TERRIFIC FINANCIAL DIFFICULTY STOP CAN YOU DEPOSIT TWENTY FIVE HUNDRED DOLLARS TO MY ACCOUNT.”

Of the handful of collected letters I own, curiously none of them drift too far from this painfully personal tone. But my limited database of Communist letters does not account for what James Thurber, who was very far from considering himself a Communist, witnessed in the letters published in the memoirs of Joseph Freeman, the editor of the Communist Party’s cultural magazine, New Masses.

Thurber’s Shoes & the Concept of a Fish

In Thurber’s essay “How to Write an Autobiography” published in his 1935 book, Let Your Mind Alone!, the humorist reviewed Freeman’s 1936 memoir, An American Testament: A Narrative of Rebels and Romantics. In it, Thurber compliments the ambitious output and intellectual rigor of the Communists—“Communist intellectuals are the most facile and articulate of all writers, and words come out of most of them like water from a faucet,” he writes—but he also detests these qualities, especially when they’re on display in letters.

One of Freeman’s letters begins with the line: “It was my idealistic, religious, artistic bias which made me blind to pragmatism.” The thousand-word letter stirred in Thurber a level of opposition typically reserved for the anti-elitist fervor of the Communists. Freeman’s letters, Thurber argued, “sounds more like an essay written to save in a file and someday print in a book.” He claimed that the letters hardly read as though they were loosely written to a friend and instead appeared read as if they were meticulously re-written. “Rewriting a letter to a girl is all right, under any circumstances,” Thurber wrote, “but that’s as far as I will go.”

Thurber was on to something, although this was hardly a new phenomenon. Pick up any anthology or “Marxist Reader” and one will find in it a slew of letters from Marx, Engels, Lenin, etc. quoted as if it were straight from the pages of a volume of Capital. In the Reader in Marxist Philosophy, Engels writes a letter to a Mr. Conrad Schmidt on the function of concepts reflecting reality. “The concept [of] fish includes a life in water and breathing through gills; how are you going to get from fish to amphibian without breaking through this concept?” Engels asked rhetorically in 1895. In an 1894 letter to Heinz Starkenburg about the “superstructure,” Engels wrote that “political, juridical, philosophical, religious, literary, artistic, etc., development is based on economic development. But all these react upon one another and also upon the economic base.” And so it goes with the casual discourse of the 19th century Communists.

The loaded tone of these letters, most of which are actually far easier to understand than the texts in their actual books—they read more as a Twitter thread than a chapter in The Poverty of Philosophy—nonetheless appear detached from the daily correspondences of an average proletarian. Thurber, hardly a proletarian in the traditional sense, nonetheless recalled a letter he once received from a well-known writer that contained only one sentence: “Will you please for God’s sake come back with my shoes?” Apparently he’d accidentally put on the writer’s shoes after a party the night before.

Thurber’s letters exhibited in the 1980 Selected Letters of James Thurber are sometimes just as lengthy as Engels but they trade his debates about base vs superstructure for those silly stories, anecdotes, and advice that the Columbus-born Thurber is known for. “Having been photographed and interviewed fifty times in fourteen months,” Thurber wrote in 1959, “I have lost weight, sleep badly, and hate photographers, especially the artistic ones who take 200 shots of their subjects at one sitting.” As a Midwesterner, he always maintained a critical perspective of New York in his letters: “A person can admire New York and so on, and all that, but I feel it is absolutely impossible to love the place,” he wrote in 1938. In his advice to a young writer, he emphasized the need for a general education. “It is also important to read good books and nobody should try to be a writer until he reaches twenty-four years of age,” he wrote, clarifying that he only started working at The New Yorker at thirty-two and the first of his dozens of books wasn’t published until he was thirty-five.

Despite his malice towards Freeman’s letters, Thurber’s letters share more in common with the 20th century American Communists than he’d likely admit. And while they had very little in common in regards to politics and historical significance—Thurber, it should be recalled, made a public stand against the blacklists and anti-communist hysteria—there remains something deeply American in the morals of all these writers—both in the way of advocating for basic liberal ideals and in the mundane topics of their daily letters.

Thoreau vs Trump vs Lenin

It was Thoreau who argued that we should do away with the post office altogether. “I think that there are very few important communications made through it,” he wrote in his 1854 classic, Walden. Yet, across the political spectrum, all sides recognize the post office as a battleground of far greater significance.

In 2020, Trump admitted to starving the US Postal Service of funds to disrupt the flood of mail-in ballots expected to dethrone him in the election. During his administration, the post office was seen as a battleground for funding social services. On the other side, it was no other than Lenin himself who, writing in his famous 1917 book State and Revolution, saw the revolutionary potential of a publicly funded monopoly as an analogy for what a socialist state would strive for:

“To organize the whole economy on the lines of the postal service so that the technicians, foremen and accountants, as well as all officials, shall receive salaries no higher than "a workman's wage", all under the control and leadership of the armed proletariat–that is our immediate aim.”

We should remember the Leninist potentials of the post office when we choose to, on occasion, write to our friends about the concept of a fish. It’s the social functioning of letter distribution that can help maintain some image of a future worth fighting for while typing or handwriting a friendly letter. Even after the revolution, there will still be room for playful, mundane storytelling in our letters. But rest assured, we Reds will never forget the words of those merchants in the thuggery. The proletarian post office will not spare a single salesman who manages to possess the qualities of both greed and wit.