Thurber in Paris

The famous New Yorker writer from Columbus, Ohio was forever changed by his time in the romantic post-WWI city of Paris.

This story originally appeared in the Columbus magazine, Refined.

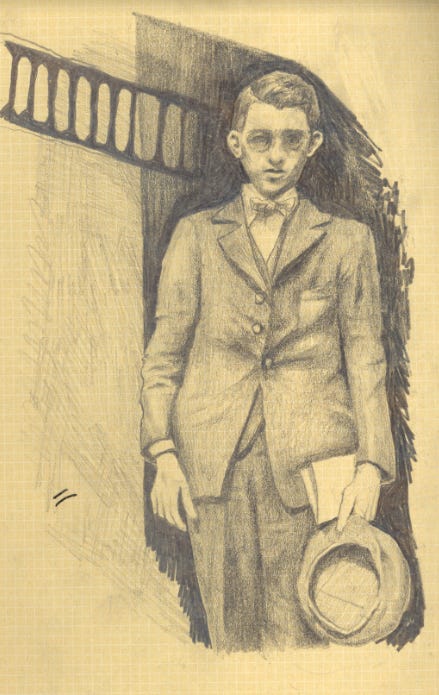

A writer is not a film star of grave visual interest, not a political figure of overarching power, not a worker of direct utility. A writer is their text, a channel that projects carefully crafted words wielded like a brush. With literary figures, the physical being is less relevant, disappointing even, than their works. They are less often the postcard of masculinity, rarely a Hemingway, and more often the scrawny man with glasses drowning, as James Thurber was, helplessly in the South of France — thankfully he was saved by a man with a wooden leg, to which Thurber asked him “to save the women and children… after he got me out.”

Insofar as Thurber’s works are concerned, they have been largely forgotten. His books are generally unknown, his articles unread. Even in his hometown of Columbus, I have found few who know his name and none who know his books. The writer, who EB White “preferred” over “Mark Twain” as a humorist, has dropped off the radar of our literary canon. But it’s his visual interest, his underwhelming power, his European adventures — ranging from the accidental setting off of a grenade to the losing of his virginity and then the finding of it again — that concern us today.

Thurber was born and raised in Columbus, attending OSU in the 1910s. Despite his middle class background, he did not have an easy life in his youth. Were it not for his brother William accidentally shooting his eye out with an arrow at seven, James might’ve graduated from OSU, leading a life that would be considered “normal” for the time, that is, going off to war and losing his eye on the battlefield. Instead, Thurber spent much of his early life as an insecure, introverted, and nearly blind fellow. It’s under these circumstances that Thurber first sailed to Paris in his mid-twenties.

That First Time He Saw Paris

Thurber’s first journey to Paris was a nauseating one. Possessing a chronic seasickness unfamiliar to a landlocked Thurber, he spent much of his time clinging nauseously to his bunk as the ship, the Orizaba, took an elusive route to avoid the remaining submarines of the Great War. On November 11, 1918, before a pale Thurber docked in St.-Nazaire, the Armistice was signed.

He arrived in Paris to celebrations. The gray Parisian Fall weather was met with the high spirits of Paris’ peace festivities. “Girls snatched overseas caps and tunic buttons from American soldiers, paying for them in hugs and kisses,” Thurber claiming that, “The Americans have never been so loved in France, or anywhere else abroad.” One of the hats that was snatched was his own. Since his trunk was left behind in St.-Nazaire, he had to buy a new suit, which was inflated both by wartime prices and a tailor who refused to deliver him anything but a vastly oversized outfit. He would go for much of the trip with a massive suit and no hat.

An eager observer and an adventurous loner, Thurber lived a happy life as a master of code — he was working as a code clerk at the American Embassy — in his slice of Paris. He did not, unlike other Americans in his position, take to the great cultural wonders of the city, those tourist destinations sought after by foreigners. Instead, he took to laughing and being impressed by the little things. He might ask someone what they’re doing and they’d respond, “going to such and such,” and he’d respond, “Well, if you change your mind, come along with me to so and so.” It was not about the art of a museum, for example, but his reaction to the art. A walk was not a walk, but a flood of senses, a downpour of youthful love and humor. When he did visit the standard landmarks familiar to American tourists, his itinerary was guided by scenes from his two-volume edition of Henry James’ The Ambassadors.

Two shocking incidents, both sparked by a clumsy trip, stuck out on his time abroad. The first scene unfolded in an environment that can best be described as bourgeois. He was at the Ritz with fellow Ohioans when he tripped over a cord and pulled down a large lamp. The room got quiet and all eyes were glued on him. When he arose, he straightened up like a baron and yelled, “Oh, what the hell!” and stomped out authoritatively.

The location of his second tripping was less serene. Thurber was touring battlefields when he tripped over a strand of wire that set off a grenade 50 feet away. He also ruined a shoe and the leg on his oversize suit pants climbing in and out of trenches and over barbed wire.

His affairs were not limited to embarrassing, almost deadly, trips. Two romantic flings blossomed in his first Parisian tenure. While he “never had a natural invisible supply of supreme confidence,” as he put it, he nonetheless maintained a love life throughout his twenties. Despite his romantic interests back home, it was in Paris where he would break his sexual purity. Ninette and Remonde, his Parisian lovers, might’ve gone unmentioned in his biography were it not for a suspicion that he “stepped aside,” or lost his virginity to, Remonde. He left Paris after 15 months, returning to Columbus in February of 1920 as a new man.

Columbus’ Lost Generation

Thurber made one more foundational trip to Paris in his late twenties. It took a good deal of persuasion on the part of Thurber’s wife Althea to get Thurber out of his comfortable newspaper job at the Columbus Dispatch. His family never expected Thurber to leave Columbus or do anything more than to be a newspaperman at the Dispatch, but Althea recognized that Paris-Thurber was not the same as Columbus-Thurber. “You can write and you must write,” she said. “You are a humorist and Columbus isn’t the place to do humor.” And so they set sail in 1925 on the Leviathan for another nauseating trip.

They sightsaw as Thurber took to tracking down freelance work. This is when he had his drowning incident outside Nice, which wasn’t “as funny as you make it out,” he wrote. They settled in Normandy as the writing location for what was to be Thurber’s first novel. The beautiful region with its gardens, scenery, and proximity to the sea, was stunted by their intimidating landlady. A “large and shapeless” Madame with a prominent mustache and a smile that “was quick and savage and frightening,” scared James, who often imagined her entering his room with a kitchen knife. On occasion, she would succeed in letting out her entire English vocabulary at once: “I love you, kiss me, thousand dollars, no, yes.”

His novel would tell the story of his friend Herman Miller with the backdrop being his beloved OSU. He attempted to combine his humor with Jamesian fragmentation and asides. Thurber, however, was sick of the characters at the end of 5,000 words. He showed the draft to Althea who said it was “terrible.” He agreed. Thurber never attempted to write a novel again.

The couple moved to the Left Bank where Thurber got a job with the Paris edition of the Chicago Tribune for $12 a week. The Paris Tribune was the troubled child, the bad boy, the more lively, yet smaller competitor to the prominent Paris edition of the New York Herald Tribune. Here in the Left Bank and on the pages of the Paris Tribune flourished a bohemian culture of writers and artists who’ve since been forgotten in the shadow of the Lost Generation. The newspaper was by and for the Left Bank, especially the Latin Quarter. This was the crowd that couldn’t afford the lifestyle of the Fitzgeralds. “We lived the typical poor man’s version of the literary life — nothing like the Hemingway set in any way,” Althea said.

It was here where Thurber developed a reputation for squeezing and twisting brief telegraphs from New York and London into the paper. The author William L. Shirer recalled that “the night editor would toss [Thurber] eight or ten words of cablese and say, “Give me a column on that, Jim.” He’d pucker up and respond, “Yes, suh.” He became a specialist on President Coolidge specifically. A short cable would come in about Coolidge addressing veterans and he’d stretch it with such imagination that it would become fiction. If chatter about Coolidge died down, he’d make up his own dispatches. He once invented an event where Coolidge addressed a Protestant church convention, proclaiming that “a man who does not pray is not a praying man.”

If Thurber lost his virginity on his first trip to Paris, he found it again on his second. His marriage became one of alienation and distance by the time he left in 1926, the year Althea would later point to as the loss of their compatibility. In tears, she told Thurber’s friend Joel Sayre, “I’ve been married four years and I’m still a virgin.” He left Paris broke and estranged from his wife, but also with the understanding that his passion was not in Jamesian fiction, but humor. Although he enjoyed his time in the grand city, he discovered that his interest was in his home country of America, not in being an expatriate in Paris.

“[Thurber] would have never written about Columbus and his family that successfully if he had stayed there,” Sayre claimed. His time in Paris shaped Thurber and his works. Were it not for the trip, not for the impression of these silly impactful experiences, he might never have created such works as My Life and Hard Times and “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” A writer might be confined to their works, but they are also shaped by their experiences. Thurber reflected on his first trip: “I think I have seen enough of Paris. Because, on final analysis, there are more things to go back for, than to stay for. My heart is in Ohio.”