When Pablo Picasso Saved Pablo Neruda

The renowned poet Pablo Neruda fled anti-Communist purges in Chile to arrive secretly in Paris. Pablo Picasso pulled some strings so he could emerge from hiding.

It was April 25, 1949, the last day of the First World Congress of the Partisans for Peace in Paris and the Argentine writer Alfredo Varela was waiting outside a prearranged metro entrance at a prearranged hour for a prearranged painter to deliver a soon-to-be arranged message that would determine the future arrangements for a hidden fugitive poet. A car pulled up and the painter-messenger, proving himself to be no other than Pablo Picasso, delivered a simple message to Varela: Pablo Neruda can now appear in public.

The fugitive Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda, had just fled from his home country after spending months underground eluding a country-wide manhunt. The poet was also a Communist senator, resulting in his expulsion from the senate and the issuing of a warrant for his arrest after President Videla outlawed the Communist Party and rounded up labor leaders. Neruda fled poetically through the Andes and, after hiding in closets, suppressing sneezes, and “borrowing” Miguel Ángel Asturias’ passport, he secretly escaped to France as a distinguished Guatemalan novelist.

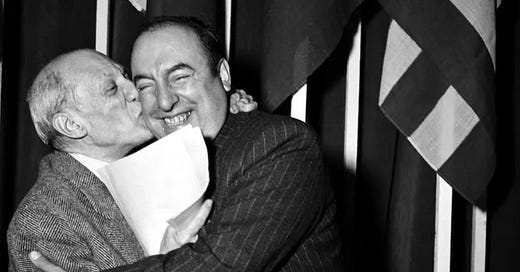

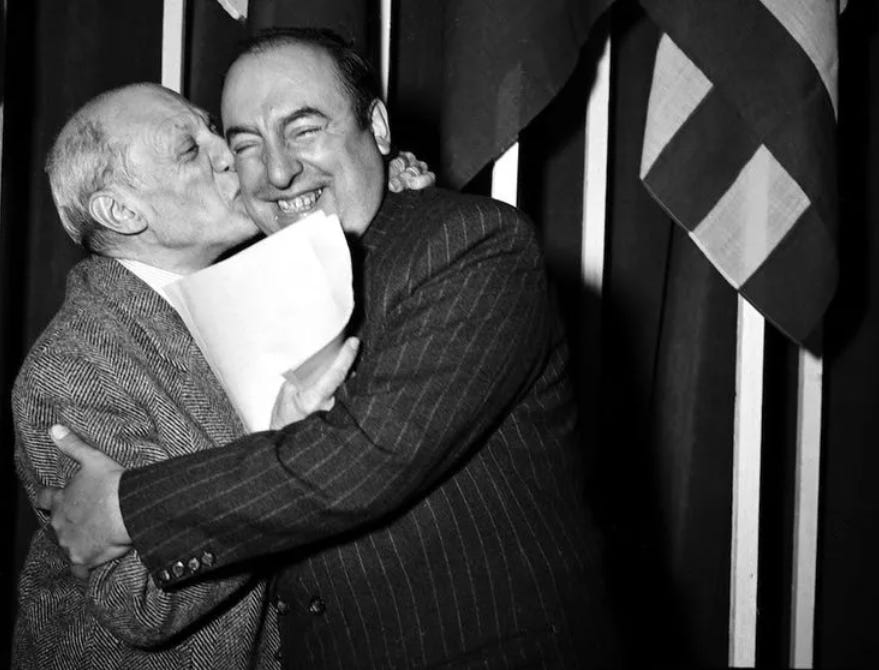

“I will give the floor to the final speaker, who will close the general discussion,” the left-wing journalist and politician, Yves Farge, said presiding over the closing minutes of the final session of the Peace Conference. It was immediately after receiving Picasso’s news of semi-freedom that Neruda rushed to speak at the congress, hoping to show face before it ended. With him, he held a thick Chilean edition of Canto General (General Song), the massive encyclopedic poetry collection that he’d been composing over the past year, the first copy of which had reached him earlier in the day—he gifted it to Picasso upon his arrival to the congress. “The man who will speak to you has only been in the hall for a few minutes. You have not seen him, for he is a hunted man… He is Pablo Neruda.”

Just as quickly as he gifted the early edition of Canto General did Neruda ask to borrow it back as he went up to the podium for his speech. Two thousand of the world’s most distinguished artists, writers, and political figures erupted in a standing ovation as Neruda emerged; among the ecstatic faces were Charlie Chaplin, W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, Howard Fast, and Diego Rivera. “The political persecution which exists in my country has allowed me to appreciate the fact that human solidarity is greater than all barriers, more fertile than all valleys,” he said before reciting “Chant to Bolivar” from Picasso’s recently acquired edition of Canto General—after the speech, Neruda kept the book, explaining to Picasso that it was his only copy.

To secure that simple message of Neruda’s freedom to speak at the congress, Picasso spent countless hours making calls and pulling strings. Neruda wrote in his memoirs that Picasso “spoke to the authorities; he called up a good many people. I don’t know how many marvelous paintings he failed to paint on account of me.”

While Neruda’s paperwork was being sorted out, the poet was bunkered down in a Madame Françoise Giroux’s apartment in the Palais-Royal next door to Collete’s. At this point, the routine of hiding was familiar to the exiled writer-politician—avoid going outside, lay low, have a backup plan, don’t sneeze. Here, he spent ample time staring at a painting of a loaf of bread that he came to adore with an unusual reverence. The large piece showed two red drapes behind a table that held, in Neruda’s own words, “an enormous loaf of bread… like the central figure in an ancient icon, or like El Greco’s St. Maurice in El Escorial.” With adoration, Neruda christened the painting with his own title: The Ascension of the Holy Bread.

It was one of Picasso’s pre-cubist paintings, one that isn’t easily found online apparently, and one that Neruda came to love. One day, the Spanish painter stopped by to visit Neruda and he happily showed him the painting. Picasso gazed intensely at his forgotten creation. After ten minutes of silent inspection, Neruda broke the quiet to say “I like it more all the time, I am going to suggest that my country’s national museum buy it.” Picasso, now looking and listening to Neruda, then turned back to the painting again and uttered, “It’s not bad at all.”

Picasso was not entirely out of his element with left-wing intellectuals and artists of that time and place. Abstract and cubist art might’ve been condemned in many socialist circles as “bourgeois” or escapist, but Picasso himself was an unapologetic Stalinist,”radiating fiercely with left-wing political views and never shying away from shouting matches about socialism. He was, by all measures, a perfect fit for Paris and its émigrés. In what was labeled his “one and only speech of his life,” Picasso spoke at the July 1948 World Congress of Intellectuals in Poland to deliver a message about the repressed Communist poet, Pablo Neruda:

I have a friend who should have been here, a friend who is one of the finest men I've ever known. He is not only the greatest poet in his country, Chile, but also the greatest poet in the Spanish language and one of the greatest poets in the world. He is Pablo Neruda.

Pablo Neruda, my friend, is not only a great poet, but also a man who, like everyone here, has devoted himself to presenting good in the shape of beauty. He has always been on the side of the unfortunate, of those who ask for justice and fight for it. My friend Neruda is presently being stalked like a dog, and nobody even knows where he is.

Our congress, in my view, must not accept such an injustice, which may be turned against all of us. If Pablo Neruda were not to recover his freedom, our congress would not be a congress of men who deserved freedom. I propose that the following resolution be approved and given the widest distribution:

The World Congress of Intellectuals, meeting in Wroclaw, send their expression of support, admiration, affection and solidarity to the great poet Pablo Neruda. The congress's 500 members, who represent 46 nations, denounce before all people the degradation of police procedures by Fascist governments who dare to attack one of the most eminent representatives of culture. The members urgently demand Pablo Neruda's right to express himself freely and to live freely wherever he pleases.

Less than a year later, Neruda spoke to the same members at the 1949 Peace Congress to show the international community that he had fled the repressive police state in Chile. A journalist interviewed him at his hotel the day after the congress, informing him that the police in Chile flatly deny his presence in Paris, claiming that it was simply a double, the real Neruda was still in Chile and the police were right behind him, they insisted. “What should we answer back?” the journalist asked. Remembering Mark Twain’s claim that William Shakespeare didn’t write anything, Neruda told the newspaperman: “Say that I am not Pablo Neruda, but another Chilean who writes poetry, fights for freedom, and is also called Pablo Neruda.”